Artist Michael Rakowitz’s new exhibition is full of gorgeous paper mache recreations of lost Iraqi artifacts, alongside major gaps in the wall. These gaps are labeled, they are part of the exhibition. Why?

Assault of Iraqi History: Looting

In the aftermath of the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, the National Museum of Iraq was raided with around 15,000 works looted. Worse, the U.S. ignored pleas to protect the museum, which was left unguarded for 36 hours. While about 7,000 works have been recovered, the majority are left unaccounted for.

Reclaiming Iraq: Activism Through Art

This led Michael Rakowitz to start the project The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist in 2007, recreating the 8,000 pieces of art that were destroyed in the 2003 Iraq Museum raid. The name comes from a direct translation of “Aj ibur shapu,” an avenue that was used as a processional gate in ancient Babylon, excavated by a German archeologist. Despite Iraqi protest, it was placed on permanent display in Berlin. This became the namesake of the project, as many Iraqi artifacts followed the same unfortunate trajectory.

Rakowitz’s team uses a range of brightly colored Middle Eastern food packaging to craft the recreations of the lost artifacts from packages like teabags, apricot paste, and date syrup. Significantly, the date syrup was made in Iraq, placed in steel cans in Syria, and then labeled and sold to the rest of the world by Lebanon. This helped Iraq get around U.N. sanctions that were causing widespread economic devastation and starvation. Like Iraqis, the wrappers themselves experienced international xenophobia, having to hide where they were from. Rakowitz sees the hidden provenance yet refusal to disappear as a form of resistance and joy.

Rakowitz uses these pieces as a “spectral placeholder” for artifacts lost, but also for Iraqi lives that have been lost. Rakowitz calls attention to colonizing Western valuation systems that mourned for the loss of these objects but not for actual Iraqi lives. His team has constructed over 900 of the lost items, with plans for the project to outlive Rakowitz and his studio.

Assault of Iraqi History: More Destruction

In 2015, ISIS released videos attacking Nimrud, a rediscovered ancient city, with sledgehammers, bulldozers, and explosives. Among the thousands of losses, the loss of parts of the Northwest Palace, where many great artifacts came from, was significant to Rakowitz and his forthcoming art.

ISIS and The West: Who Destroys More?

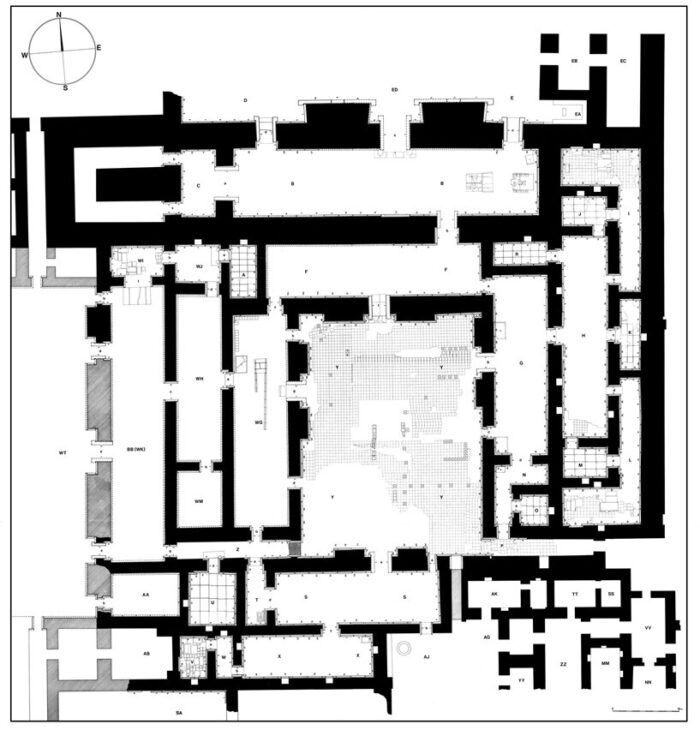

Rakowitz expanded his The Invisible Enemy project to include the destroyed artifacts from the 2015 ISIS attack on Nimrud. In his lifesize exhibitions, Rakowitz puts the viewer in the position of an Iraqi in the Northwest Palace the day before it was destroyed. His reconstructions follow the floor plan of the palace itself, where Rakowitz places his reconstructed artifacts alongside large gaps, representative of objects that were violently taken from Iraq by the West. This points to the history full of gaps and fractures that Iraqis are forced to make sense of, as colonialism takes the form of cultural robbery in the name of “science” and excavation. In reality, while claiming to “protect” history, European archaeologists throughout the nineteenth century have hauled thousands of Iraqi artifacts into their own countries, ripping away Iraqis rightful past. Rakowitz is mourning the loss of all that ISIS destroyed, while also maintaining that ISIS is not the only group that has violated Iraqi cultural heritage. Rakowitz hopes to eventually reconstruct every room in the palace.

Rakowitz’s Room H of the palace is currently on display at the Wellin Museum of Art. Rakowitz uses his reconstructions to honor missing and destroyed artifacts, while using literal gaps in his exhibition to hold a critical stance towards the robbing of Iraq by the West and museum world. By the time ISIS got to Nimrud, it was had already been irreversibly harmed by the West.

The art museum is far from a neutral observer. On the contrary, it is often a site of violence and disregard for cultures outside of the West. The next time you go to a museum, ask the questions, where did this come from? How did it get here? Why?

Often, there is an alternative narrative, one rich of culture and beauty but singed with pain and violence, that can never be simply captured on a Western wall label.

Jessica Rosen is an Art & Art History major and a Women’s Studies minor at Colgate University. Her research investigates the implementation of diversity initiatives in art museums.