Citizens of the Western world in the modern age live in the most productive, aesthetically accomplished, and technologically advanced society to ever exist. Modern westerners regard themselves as the result of a continuous chain of development, from the barbarism and infancy of prehistoric tribes, to the impressive monuments and works of early civilizations, all leading up to Burberry-wearing business people in air-conditioned offices – enjoying the fruits of our advanced society. We believe that all of history has been a progression towards higher and higher forms of civilization and that we represent the current cutting edge of human development.

David Wengrow (left) and David Graeber (right)

The Critique

This conception is beginning to falter in light of current academic questioning. Archaeologist David Wengrow and anthropologist David Graeber posit that we should rethink what constitutes advancement, what defines civilization, and, as an extension, the true nature of our own societal structures. Following in the footsteps of social theorists such as Emile Durkheim and Marcel Mauss, Wengrow and Graeber propose that a more accurate conceptual understanding of civilization does not prioritize the monuments, technologies, and great works of a given society. Rather, civilization is better thought of as a metric determined by the level of cross-cultural exchange, non-coercive social cooperation, and mutual aid within a society.

In their 700-page retelling of human history, The Dawn of Everything, Wengrow and Graeber postulate that paleolithic humans were not unintelligent or even non-political. Early systems of social organization were a conscious and informed decision made by civically minded individuals who understood and were capable of conceptualizing alternatives. Early peoples could have developed hierarchical, dominating societies, but chose to not. For example, in an early neolithic settlement located in central Turkey, all archaeological evidence demonstrates a commitment to horizontal organization. Dwellings and artifacts demonstrate similar levels of wealth between family units and a simultaneous diversity of lifestyle and apparent freedom. More influential individuals were not grouped into given living areas to form elite neighborhoods. People in this early town made a conscious choice to build a society that remained committed to hunting and foraging and did not allow for social stratification. With this in mind, the idea of a progression from “barbarism” to “civilization” seems inaccurate.

The history of civilization is not a history told by monuments and ancient art pieces. Many of the great works of ages past were only possible due to the structures of fundamentally unequal and violently coercive societies. Wengrow and Graeber note that the “strong and stable government” of historical Egypt was possible because of the “crippling taxation, state-sponsored suppression of ethnic minorities, and the growth of forced labor to support royal mining expeditions and construction projects—not to mention the brutal plundering of Egypt’s southern neighbors for slaves and gold”. While this is only a single example, it demonstrates the larger takeaway of the idea. Why should we mark a society’s level of civilizational achievement by its monuments, works of art, or high culture – when these things are the evidence of the very opposite of a civil, mutually cooperative society?

What it means for us

With this in mind, we must re-evaluate the way we have structured our own society. Just as tribal bands were not the only option available to paleolithic peoples, our current societal organization is not inevitable, unchangeable, or without alternatives. Are we civilized? Do we demonstrate cross-cultural exchange, non-coercive social cooperation, and mutual aid?

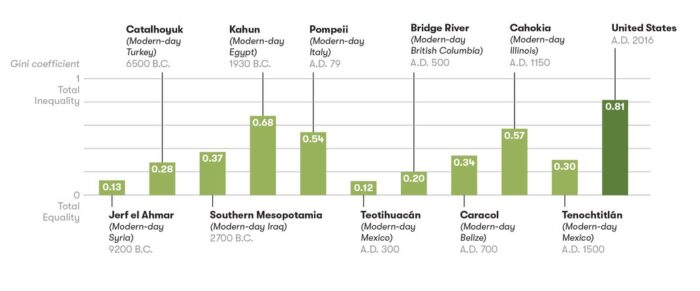

I would argue that no, we do not. Modern western society broadly, but the United States more specifically, has a higher level of social stratification than nearly any other cultural group in world history. Arizona State University archaeologists used physical evidence and the remains of human dwellings to calculate the level of wealth inequality at a variety of archaeological sites. These societies, often conceptualized as repressive and backward, express a greater level of social equality than the United States.

Similar studies, done with different methodologies and analyzing different cultures, have come away with similar conclusions. A 2010 study done by Walter Scheidel and Steven Friesen found the U.S. has a higher level of income inequality than the Roman Empire in 150 C.E. The existence of Pyramids and Pantheons evidenced a socially-toxic concentration of power in the ancient world, but personal space programs and super-yachts show the same thing today. In a country where 61% of the population lives paycheck to paycheck, this is thoroughly uncivilized. Until we refocus our society toward mutual aid and ensuring the needs of all are met, we cannot consider ourselves civilized.

This leaves us with a choice. Will we continue to follow in the footsteps of the pharaohs, propagating a stratified society more interested in building monuments to hierarchy and domination than creating bonds of cooperation and coalition? Or, will we take a more paleolithic approach, and reform society to chase a newer, better idea of civilization?

The Author:

Tanner Harmon is a Colgate University Freshman from Whitefish, Montana, hoping to major in Sociology and Economics. Tanner plans to pursue a career in politics and activism.