Humble Beginnings

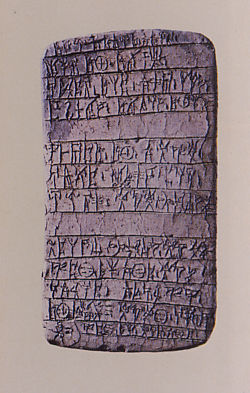

In 1903, archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans concluded his bout of excavations in Knossos, capital city of what would become known as Minoan Crete. This excavation would serve as the very basis of the understanding of the Minoans, one of the most prosperous Bronze Age civilizations. At Knossos, Sir Arthur Evans and his team uncovered the Palace of Minos, many tablets that still have yet to be translated, and, most importantly for speculations around Minoan culture, statues depicting Snake Goddesses. It is crucial to note that the story of the Minoans didn’t just reveal itself with the discoveries. Taking a step back following this excavation revealed a jigsaw puzzle of information that had to be sorted to uncover the full picture of Minoan civilization.

Putting the “Construction” in “Reconstruction”

Usually, these different pieces of history would be left up to public imagination, left well enough alone in their disjointed glory for others to fill in the gaps. However, Evans realized that here he had all the power of telling a story. This was done under the guise of a “restoration” of the site of Knossos and the Snake Goddess statuettes. Through this divisive restoration, parts of the Knossos palace were completely reconstructed in modern styles. Compounding this issue is that Evans had consulted three different people to lead reconstruction efforts, each with different approaches and with their own personal touches to add to ancient history, leading this already unfaithful-at-best rendition to be even further divorced from its original state. This trend was then carried over to the statuettes, although arguably in an even more invasive fashion.

Two Snake Goddess statues are confirmed to be real. However, even this simple fact has some footnotes. The most well known of the statuettes is one depicting the Mother Snake Goddess. The statuette was originally found missing its head and right arm. Of course, Evans couldn’t have this and promptly hired a team of artists to “faithfully” reconstruct the goddess. The team constructed the right arm as a mirror image of the left, with both hands of the Goddess carrying snakes. A crown was reconstructed seemingly with no reference to anything else found in Minoan culture, then, for good measure, a cat was added on top with no actual documented purpose. With this much work done to it, speculating anything off this “restored” version of the statuette was less personal interpretation and more an encouragement to buy into whatever Evans had in mind.

Desired Narratives

Although some could argue that Evans’ choices were somewhat based in reality, the leaps he makes can be cynically attributed to the desire to tell one very specific story. This revelation about Evans’ work was first formally exposed by Kenneth Laptatin, who noted how the narrative being presented through these “reconstructions” and forgeries weren’t without ulterior motives. For one, the Mother Goddess was already a popular theory in explaining the belief system of the prehistoric era. Evans had, himself, previously theorized that the pre-classical Greeks worshipped a Mother Goddess, long before he had started his excavations in Knossos. The desire for a culture worth exploring and theorizing about is also a factor itself here, as what better claim to fame than a civilization shrouded in rich culture and mystery. As Minoans are considered a part of Greek early history, any signs of advanced art are a win for the “wonders of Western civilization” crowd, as well. In this sense, Evans was just making history parrot narratives we’ve all seen before.

Fakes To Follow

A huge part of the Minoan goddess story are the many forgeries that would seek to reinforce the matriarchal theory. To begin with, few of these forgeries were believed to hold any water, as they had different methods of construction upon closer examination. More interestingly is who these forgeries were coming from– people close to Evans. Evans had originally requested and allowed for the creation of replicas of Minoan statues, which led to the totally unrelated increase of new, “authentic” statues being found. Evans had irrevocably blurred the line, and the first two are the only ones to be verified, as they were found in controlled excavations.

Blame Game

Now, I couldn’t go as far to say that Arthur Evans was the procurer of the forgeries, however, I think it is fair to say that he surely facilitated the growing market for misinformation surrounding Minoan culture. Of course, as the main source of all things Minoan, he had free reign to tell whatever story he wanted, especially one that confirmed all his preconceived notions about Minoan society. How quick he was to adopt these forgeries just because they reinforced his own vision of the Snake Mother Goddess, to me, is a move that makes him just as involved with the forgery process as those who actually carved the statues. We’ve seen similar psychologies with other forgers, such as James Melaart. Both Melaart and Evans were storytellers of some kind, with them having the same purpose of being the one to break through with some kind of historical discovery. Melaart had his Sea People and Evans had the Minoans, only the Minoans were a real civilization that forever have a false history imposed upon them.

The Author:

McKenzie Broussard is a part of Colgate’s class of 2026 from Dallas, Texas. As an aspiring art major, McKenzie takes interest in the stories told by art and what the narratives we impose on the works we see says about us as a society.