Iraqi National Museum Deputy Director Muhsin Hasan Grieves the Loss of Irreplaceable Artifacts

Wild Beasts Escape Their Spotlight

On the morning of April 10th, 2003, Iraqi citizens turned on the news to find a lion and bull displaced from their rightful habitats. Widespread civil panic gripped the country and public officials immediately organized search parties. Only these animals were not living: thieves seized the historical Ninhursag Bulls and Lioness Attacking a Nubian plaque, along with thousands of other priceless artifacts. The infamous looting of the Iraq Museum in Baghdad disrupted the world for years to come. The Iraqi government worked alongside the United States to locate the artifacts and implement international safeguards preventing a repeated robbery.

Lost and Found Artifacts

In 72 hours, thousands of heartless, treasonous Iraqis looted and ravaged around 170,000 antiquities from the Iraq Museum. How could dutiful citizens justify erasing history through looting items from their own culture?

Andrew Lawler helped assess the state of the museum a month after the looting. He recalls walking into frightful disarray: overturned furniture, splintered walls, and vandalism were omnipresent. He grieved while recounting “small fires destroy[ing] offices, and in the display area, angry mobs had shattered cases and smashed 2,000-year-old statues,” in his statement on the emotional experience.

The thousands of stolen artifacts include The Gold of Nimrud collection, the ancient Warka Vase and Mask of Warka, the Golden Harp of Ur, The Bassetki Statue, Lioness Attacking a Nubian, and the twin Ninhursag Bulls. The latter two may never be returned, along with many other missing items. Eventually, more than half of the recovered items were returned to their rightful place in the museum, thanks to Marine Colonel Matthew Bogdanos and Iraqi archaeologist Dr. Donny George. The international duo famously issued an amnesty to any looters returning museum property and rehabilitated the museum.

Plot Twist: How did this Happen?

Contrary to popular belief, officials suspected the attack, and looters are not the party to blame. Due to anticipating thievery, museum officials luckily hid 8,400 artifacts in secret locations beforehand. Brian Rose, the former president of the Archaeological Institute of America, “developed a training program for the U.S. troops who would be responsible for protecting historical sites” at risk. The beginning of the Iraq War provided a clear opportunity for looters, yet the trained American troops stationed a few hundred yards from the museum stood idly by until days after the crime stopped.

While we could continue to discuss the cultural heritage at risk in Iraq, we must first understand how the well-established art market in the west contributed to the looting. As Rose is an esteemed archaeologist, he understood that the Iraq Museum was a target for looters; every ancient artifact in the museum would successfully shepherd tremendous profits in European Auctions.

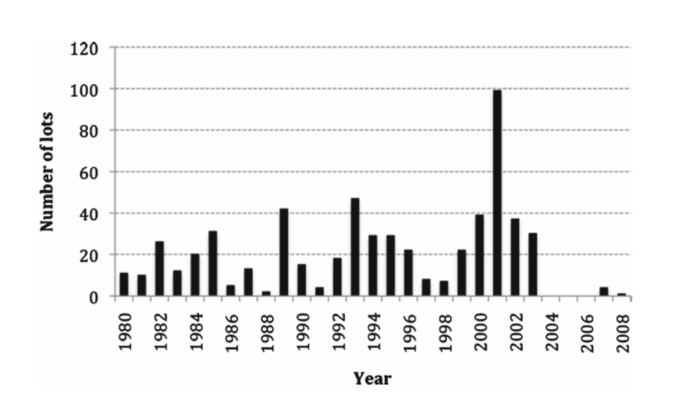

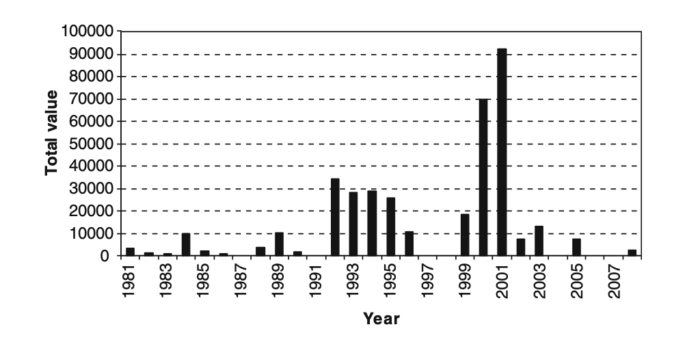

European and American art markets have thrived on old-world antiquities for decades. Consumer enthusiasm and demand paired with a lack of regulations provide a platform to auction highly valuable artifacts in unaffiliated western countries. Blame the commercialized auctions of middle eastern artifacts for the inhumane looting in countries such as Iraq. The rise of online auction platforms, such as Sotheby’s and Christie’s annually auctioned collections of undocumented cylinder seals and cuneiform objects for those willing to allocate millions for the praised artifacts. The average market price and quantity for antiquities peaked in 2001, two years before the United States invasion and Iraq Museum looting. Therefore, it is impossible to blame Iraqis for looting when westerners effectively kindled a profitable market for their artifacts. The success of international auctions undeniably led to the upsurge in looting in the Middle East.

Fast Forward: International Effects and Action Plans

Twelve years without access to the Iraqi Museum disconnected many Middle Eastern children from the significance of the societal cradle in which they reside. Yet, the responsibility of global citizens to protect history, especially from Earth’s earliest civilizations, has been widely overlooked, as Baghdad continues to suffer the effects of violence. Although looting has subsided at the museum, it still occurs within the controversial practice of auctioneering. To highlight the absurdity of these sales, I will underscore the Guennol Collection, collected by Alastair Martin. He auctioned the Guennol Lioness through Sotheby’s in 2007. Profiting off of his unjustifiably owned 5,000-year-old limestone statue for $57.2 million was not Martin’s sole option; he could repatriate the statuette to Iraq, or even donate it to the British Museum. Nevertheless, a private buyer with no connections to the piece now “has the distinction of owning one of the oldest, rarest, works of art,” produced in ancient Mesopotamia.

Did Americans learn anything about the consequences of placing incredible value upon the market for ancient antiques? Apparently not. Americans and Europeans took egregious actions within the art market, which counteracts the western media’s ability to paint Iraqi looters as savage and barbarian. If we truly believe looting is repugnant, we should, in turn, demonetize artifacts to discourage unlawful destruction of history.

Tess Dunkel is a freshman from Atlanta, Georgia. She plans to double major in English

and Art & Art History.