A message from the afterlife by Nebamun’s all-knowing Ancient Egyptian painters.

Dear British Museum,

It has come to our attention that you’re in possession of our artwork, and we have some complaints.

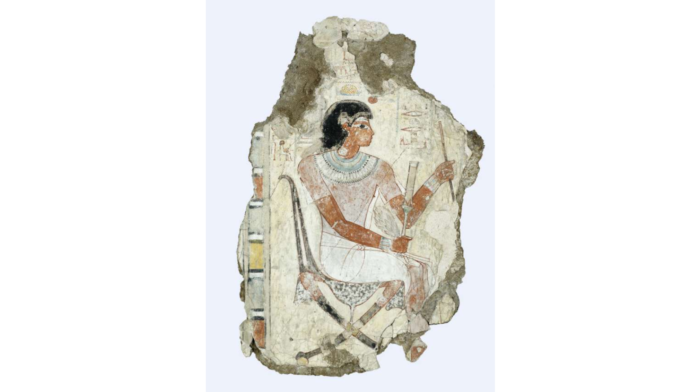

OUR CLIENT

We were hired by Nebamun, an upper-class man who died around 1,350 BCE. During his life, he worked at the treasured Temple of Amun and held the title of “Scribe and Grain accountant in the Granary of the Divine.” He was married to a woman named Hatshepsut, and the couple lived together in Thebes with their son and daughter

OUR SACRED RESPONSIBILITY

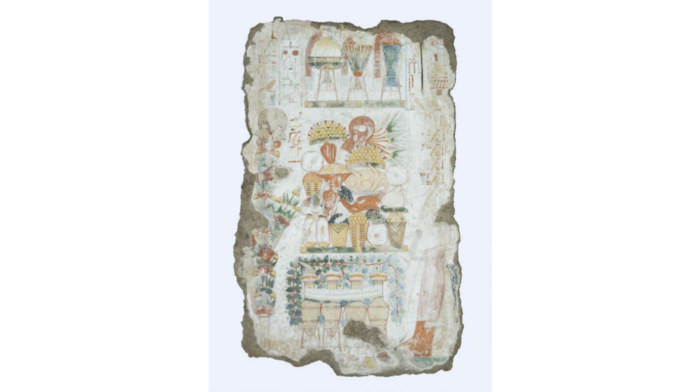

We take preparation for the afterlife was very seriously in our culture, and as painters, our work serves both a religious and memorial purpose. First and foremost, our duty is to preserve the spirit of the dead through our artwork. We believe that scenes depicted on the walls of tombs will carry over to the afterlife, both helping the individual arrive through the presence of certain gods or goddesses and giving the soul activities to participate in once it arrives. So, we strive to give our customers paintings that represent the lifestyle of their dreams, an illustration of the idealized life Nebamun aspires to obtain in the afterlife. That being said, some of the art is rooted in Nebamun’s time on earth, as the paintings are also meant to commemorate his life. When family members come to the unsealed chapel part of the tomb where these paintings are, our art’s purpose is to remind them of the great life Nebamun led.

THE CREATION PROCESS

Decorating a tomb chapel is no simple task. The entire painting process takes years to complete, and we have to do hours of prepping on the walls themselves before painting can even begin. We also make our own paints by grinding up minerals in combination with plant gum, a commonly used binding medium.

OUR MASTERPIECE

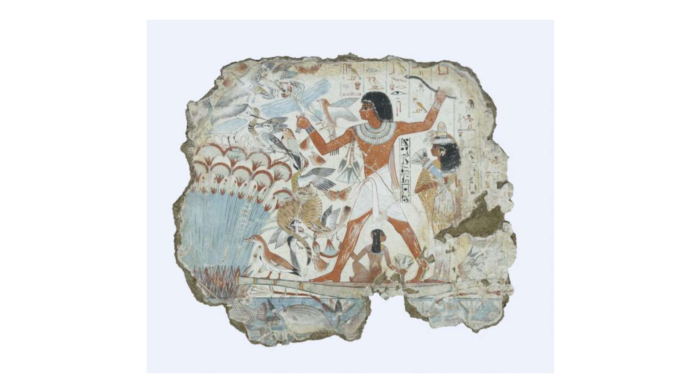

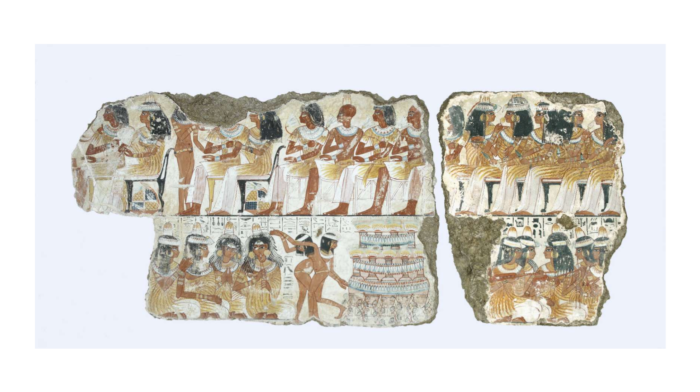

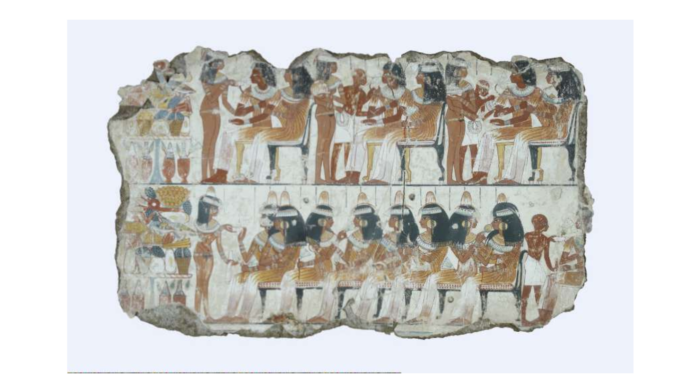

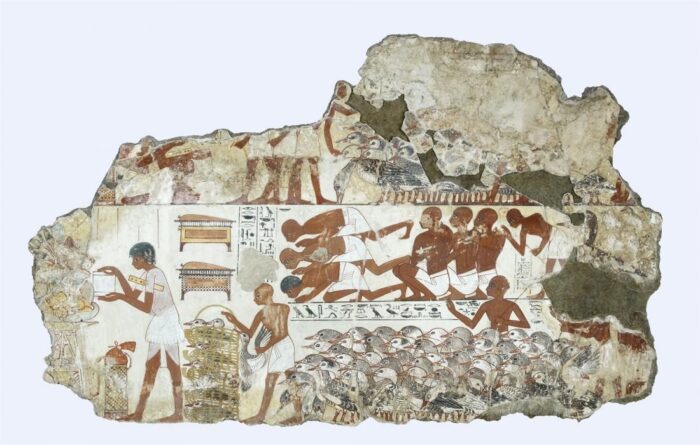

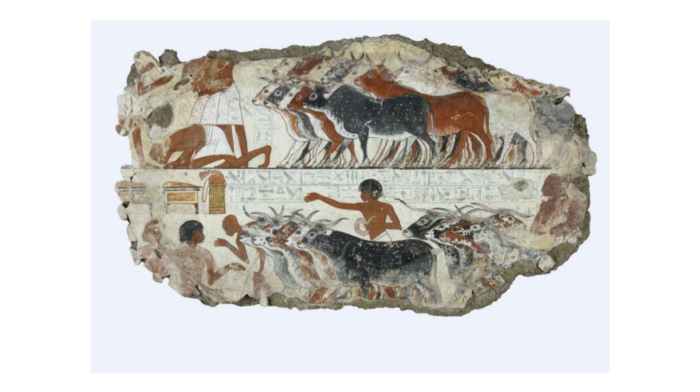

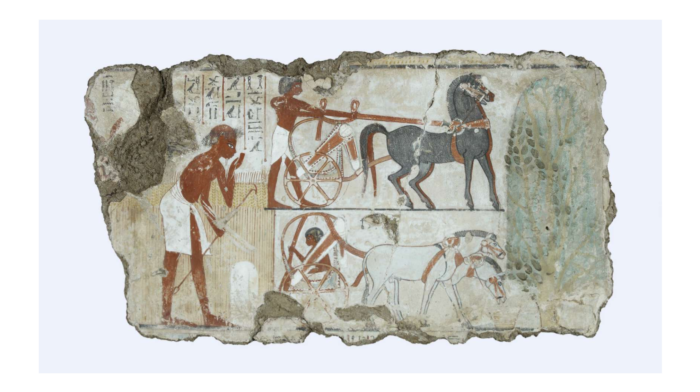

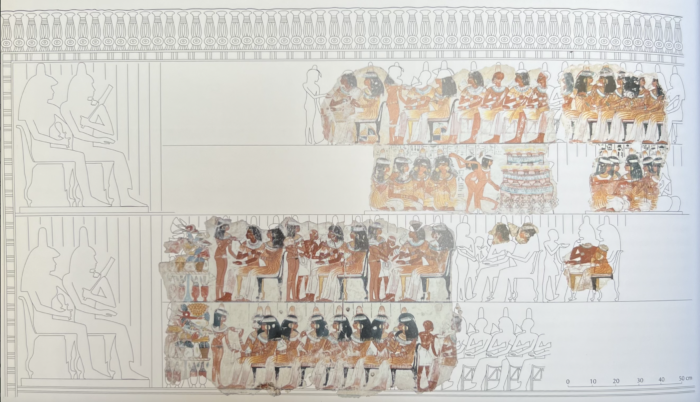

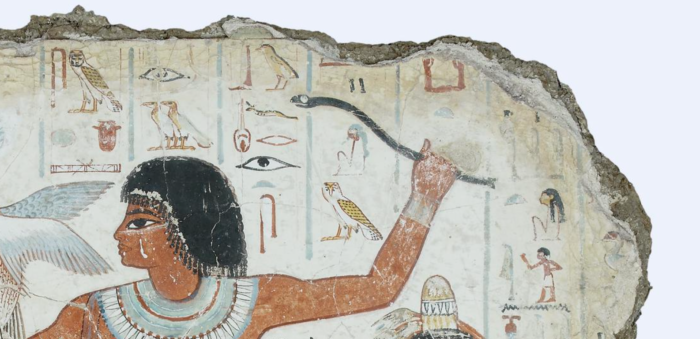

Look at how beautiful they are! Look at the intricacy and the colors! Isn’t it such a shame that these fragments are all thats left of the entire room we painted…. Anyways, one of our best scenes is “Fowling in the Marshes,” which depicts Nebamun hunting birds in the marshes of the Nile with his wife and daughter. The fertile marsh is seen as a place of rebirth, and the hunting of animals symbolizes Nebamun’s triumph over the forces of nature as he is reborn in the afterlife. We made Nebamun really big to highlight his importance in the scene. Some have argued that the tawny cat hunting alongside Nebamun is a family pet, but they’re wrong. It represents the sun-god, hunting enemies of light and order. The cat’s eye was originally gilded, which connects to the gods because they are associated with gold. The fine details of this scene are another reasons why it is so well known in the modern world, and why we are occasionally compared to Michaelangelo by art historians.

STOLEN AND DESTROYED

Our work remained untouched for nearly 3,000 years, until an idiot Englishman named Henry Salt violently disrupted that peace. He had the audacity collect and sell to the British Museum 10 of the 11 fragments they currently possess. To remove the paintings from the tomb, Salt and a companion recklessly hacked into the wall with knives and saws, then ripped the chunks of plaster away with crowbars. Traces of these savage cuts can still be seen on the pieces.

Salt sold our artwork for the insultingly low price of €2,000, which didn’t even cover the cost of procuring the paintings in the first place. He also did not document anything about the tomb; Salt died being the only one knowing its location besides us, so the tomb and everything else inside are lost to this day. To make matters worse, Salt only chose fragments that suited his Victorian tastes, completely disrupting the religious message of our art and the cohesive world we tirelessly worked to created for Nebamun.

HORRIBLY PRESERVED

To pour more salt in the wound, further damage was done to our artwork in an attempt to preserve and display it. The wall fragments varied in thickness due to Salt’s ruthless excavation tactic, so the British used plaster of Paris to create a solid mount for the art. This was a terrible idea. The thick molds used to contain the plaster were wooden, so when the water in the plaster evaporated, it had nowhere to go but through the mud and painted surface itself. This created a hideous yellow-brown mark scarring the outer 5 cm of the fragments and small cracks throughout. New backs have been applied, but the damage remains.

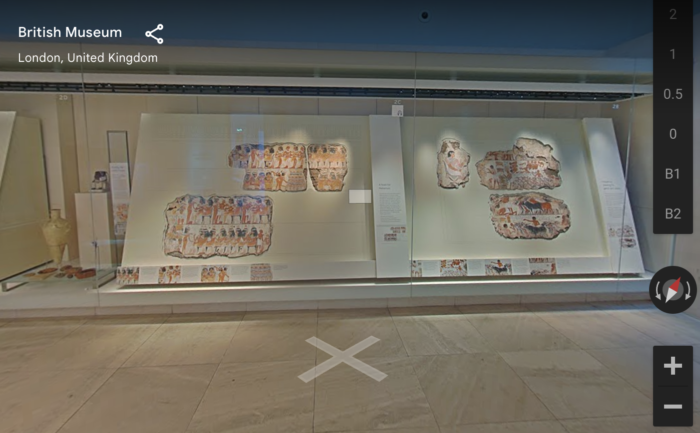

All 11 pieces remain on display at the British Museum today, so they continue to profit off of our talent and years’ worth of labor.

So England, if you’re going to continue to rob countries of artwork that are crucial to their culture and heritage and put it on display for your own benefit, you best put in a smidge more effort and care to ensure that it is done properly.

Sincerely,

Nebamun’s Mystery Artists

Lindsay Hess is a member of the Colgate University Class of 2026. While currently undecided, she has always had a passion for art and plans on minoring in art and art history. Being an artist herself, Lindsay was intrigued by how little we know about the identities of Ancient Egyptian artists and was very upset by the way the paintings from Nebamun’s tomb were cared for. This prompted her to write from the perspective of the artists.