Growing up, I would take trips to the Smithsonian and revel in artifacts from all over the world. I would visit the Statue of Liberty and know it as a welcome into the country for all of the immigrants who have traveled here, including members of my family who brought me the life I have now. Never once did I stop and consider what it would be like if those monuments were just taken away, or how the descendants of different civilizations feel about their artifacts being in countries far away.

The actual reconstruction of Ishtar Gate in the Pergamon Museum

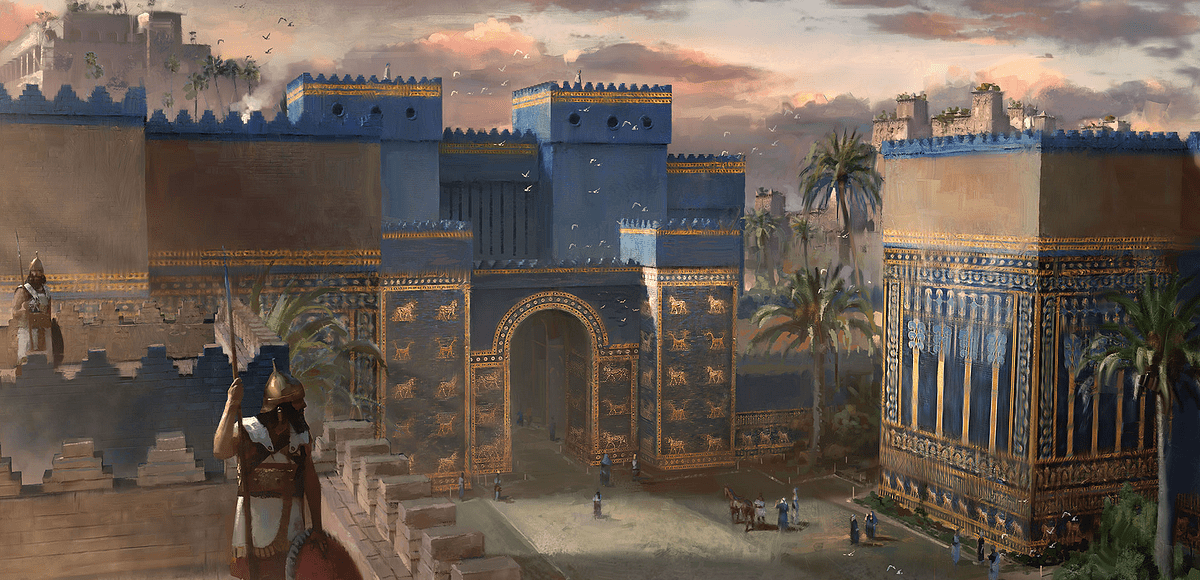

The Entrance to Babylon

Twenty years ago, Iraq put in an appeal to get their antiquities back from Germany, including the Ishtar Gate that stands tall in the Pergamon Museum. The Ishtar Gate was built during Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar II’s reconstruction of the city, turning it into the most well-known city of its time. Many people think that it should be considered one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. The gate incorporates symbols of important gods: Adad, the weather god, as a bull; Ishtar, the goddess of fertility, love, war, and sex, in the form of a lion; and a dragon for Marduk, the patron god of the city. It served as an entrance into the city, protecting the inhabitants and showing the incredible development of this civilization under Nebuchadnezzar, as well as possessing physical, magical, and ideological power.

The replica of the gate in Hallah, Iraq

The gate gradually disintegrated after the collapse of the Babylonian Empire in 539 BC after the city fell under the control of the Persian Empire. German archaeologists uncovered the remains of the gate from 1899 to 1917, and sent 800 crates of the debris to Berlin. During this time, Iraq was under the rule of other nations, the Ottoman Empire and then Britain, so many artifacts were allowed to go to countries that excavated them, giving Iraq limited control on what happened to them. After excavators collected the debris, they spent many years reconstructing it with its original pieces, turning remnants into full bricks, and then sorting them based on their colors and motifs, as well as mixing them with some modern bricks to fill the gaps.

Germany continues to withhold the monument despite Iraq’s appeal. Although some argue that Iraq could not keep this artifact safe due to the country’s instability, I do not think that is our choice to make for them: the descendants of the creators and people who truly understand its significance. It is now used to fit whatever narrative the museum wants it to fit, rather than its historical value. The Pergamon Museum, known to some as a museum of architecture, has used this piece to guide the visitors through history and show off the antiquated architecture, separating it from its intended value, but giving it “its uniqueness and ubiquity,” by the use of “modern display and framing.” While this is definitely beneficial in making this piece iconic and promoting people to learn about it and its culture, it is already one of the most stunning and well-known pieces, so it would still have a notable reputation if it were to be moved back to Iraq.

America’s to Blame

It is easy to view the problems between Germany and Iraq as an outsider, but it is a different experience when I hear that the US is also involved in the destruction of the memory and culture of the past. As a US citizen for my entire life, I have been sheltered from many of the wrongdoings of our country in recent years. It was not until I saw that officials from Iraq all agree to blame Americans for the damage to historical sites, including the replica of the Ishtar Gate in Hillah, Iraq, that I realized I still had to learn about our country. While the United States has agreed to pay $800,000 to restore the site, the damage to the remnants of the civilization “could never be repaired or adequately compensated for.” I agree with that statement, as there is no way hundreds of years later to accurately restore that piece of history that was lost. Additionally, 15,000 artifacts were looted from the museum in Baghdad following the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, and as of 2018, only 7,000 had been returned. What may be even worse is that compared to Saddam Hussein, who tried to rebuild the site in his own egoistic way, Americans still did worse by Babylon, according to the director of the ruins Maryam Musa.

Iraqi student in front of the Ishtar Gate in Berlin in 2013

Finders Keepers?

Despite arguments for keeping the Ishtar Gate in Germany to allow people outside of Iraq to experience the beauty of the piece, it is not fair to take that opportunity away from their descendants to keep it in its original place. I would never want the heirlooms or art that my family has to be taken from me and put into a museum halfway across the world, and it should not be normalized just because someone else dug it up and found it first.

Allie Giller is from Wilton, Connecticut and is a freshman at Colgate University. While she looks to major in economics or environmental economics, she is fascinated with history and how people developed to where we are today.