Jesus Enters the 4th Dimension

“And they crucified him,”

(MARK 15:24)

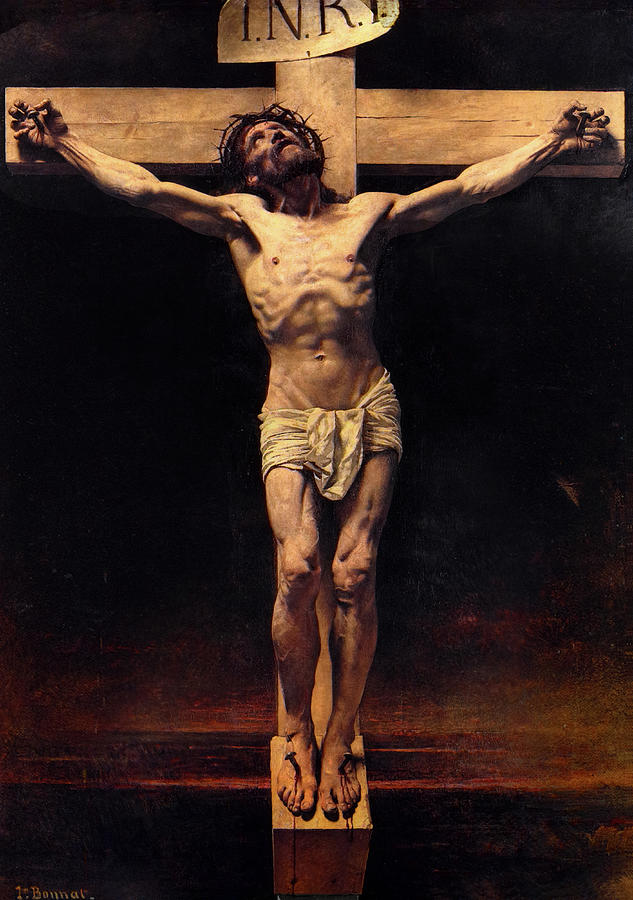

As a child, I tried fruitlessly to entertain myself during hour-long masses by any means possible. Yet, my wandering eyes were always met with a bloodied, solemn crucifixion. With pain and agony so palpable on his face- the gaping side and crown of thrones dripping with blood- I was always whipped into attention.

Grotesque, hyper-realistic depictions of the crucifixion are all too common, which diverge from the original text in the Gospel of Mark. Unlike these overused retellings, Salvador Dalí’s 1954 Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus) defies these norms and honors the original text.

While other afterlives are far removed from the original, often representing a bloody, agonizing scene as depicted in the Gospel of John, this stripped down version of the crucifixion aims to revive traditional religious values with a scientific flare, and flare it has.

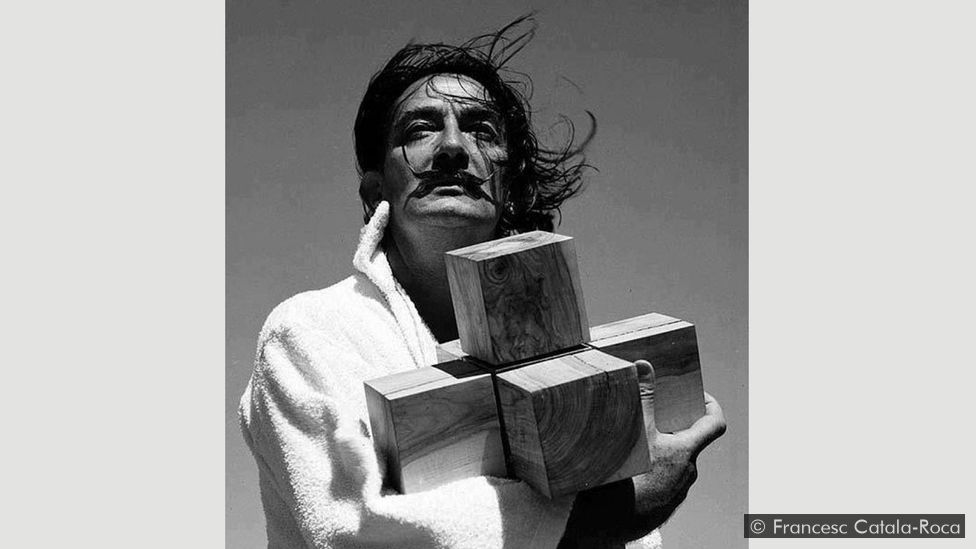

Painted during an age of rapid scientific growth after World War II, Dalí speaks to believers and nonbelievers alike. The artist explores the growing divide between the spiritual and scientific worlds, still brewing today, as he attempts to foster coexistence.

Dalí’s futuristic take on the crucifixion of Christ grew from an interest in the Nuclear Mysticism movement of the 1950s, which sought to combine religion, mathematics, science, and Catalan culture. Through the muted lens of the Gospel of Mark, the artist’s main message was to further affirm the divinity of God in a perplexed scientific age, still reeling from their new weapons of war.

Toned-Down Torture

Most crucifixion afterlives show Christ in bloody agony– emotions clearly palpable on his face. Rather than honoring Mark’s retelling, these mirror the account retold by the Gospel of John, as this scripture describes similar bloodshed.

“Then Pilate took Jesus and had him flogged. 2 The soldiers twisted together a crown of thorns and put it on his head. They clothed him in a purple robe 3 and went up to him again and again, saying, “Hail, king of the Jews!” And they slapped him in the face.”

(JOHN. 19:2-3)

Dalí portrays a healthy, undamaged, and almost invulnerable levitating Christ, which brings to light a new appreciation for the muted retelling of the Gospel of Mark. In the original text, without describing any of the gruesome details, the Gospel of Mark simply declares, “they crucified him.” (Mark, 15.24) By showing a Christ completely devoid of wounds, not only does the artist honor the original, Dalí emphasizes Jesus’ ability to rise above earthly sufferings.

Also, while the pain on Jesus’s face is very apparent in modern afterlives and in the Gospel of John, his face is obscured in Dalí’s artwork, as we are almost impervious to his suffering. Again, this lack of visceral, outward pain is similar to the original text.

The 1954 work converges the crucifixion and ascension into one scene, as Jesus’s body seems to be already healed from his torture on Calvary. The focus shifts to his glory, rather than his human suffering. While this addition of ascension diverges from Mark, the idea that Jesus’ crucifixion is an honorable and fulfilled event rather than a tragic, humiliating accident remains the same.

Rationality of Science

While scientific interpretation and faithful retellings of ancient texts don’t seem to go hand in hand, Dalí’s scientific painting proves more faithful to the original scripture than works with a more “traditional” take. In fact, by remaining true to the Gospel of Mark, Dalí is able to further strengthen the bond between science and religion.

Hyper-realistic Hypercube

Rather than a traditional wooden cross, Dalí uses a prominently displayed hypercube. The highly-accurate interpretation of a physical object mirrors Mark’s logical depiction of the event. Instead of emphasizing the weight or burden of the cross, as modern afterlives often do, the cross’ multi-dimensional form levitates Christ, rather than burdening him.

Therefore, this cross is not represented as an evil shackle. The hypercube symbolizes the three dimensional human form of Jesus, God, and the Holy Spirit. Just as God exists in a universe incomprehensible to humans in a transcendental nature, so does the hypercube’s dimensions. Both are equally unattainable. This revolutionary take on such a classic scene portrays Jesus’ crucifixion how the Gospel of Mark intended.

Modern with the Mundane

To further support the unification of two seemingly separate and incompatible theories of religion and science, the artist blends the contemporary with the classic. The modern cross and the title “corpus” which refers to Christ’s body and geometric shapes is paired with the traditional draping on the woman’s garments. As always, these details remain faithful to the text, as women watch in reverence.

Beam Me Up, Scotty

Lastly, as Jesus is being taken to another dimension, this biblical scene is shown in mathematical and scientific perspective. This idea of the transcension of time and space is a common thread throughout Dalí’s works. By merging the two events, Dalí argues that Christ is the Lord for all eternity, not bound by the limitations of time.

While drastically modern, all of these scientific additions support Mark’s straightforward sentiment which portrays the crucifixion in the simplest form possible. Instead of stones, Dalí uses an even, logical chess board on a barren landscape. Instead of gore and complex emotions: serenity.

Cassey Bennet’s analysis of The Prince of Egypt mirrors this retelling of a biblical scripture for the modern age that honors the spirit of the original text. Both interpretations attempt to reconcile ancient stories with values and ideas that we care about in the present, without any concern for preserving historical accuracy.

A Well-Needed Transfiguration

After 2000 years, the interpretations of this ancient doctrine are many, but retellings that truly capture the plasticity of the bible are few and far between.

Although 4th dimensions, chess floors, and a levitating Christ seem anything but rational, Dalí drags the viewer from the messy and emotional realities of endlessly replicated afterlives into his logical, groundbreaking interpretation.

Paige Halverson

Hi! My name is Paige Halverson, and I am from Dallas, TX. I am interested in the sciences and art history, and I plan on majoring in neuroscience and minoring in French. I love to play tennis with my sister, go on long walks with my dog, and cook with my mom.